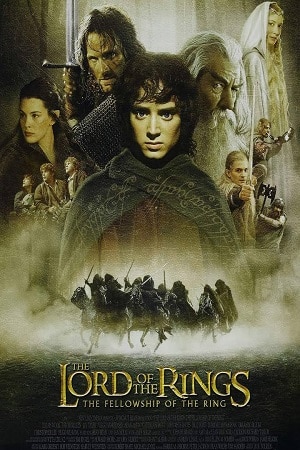

A Look Back: The Lord of the Rings

I grew up reading JRR Tolkien. I read The Hobbit (1937) in 1982 (and played the adventure game for the home computer). That summer break, I read The Lord of the Rings – The Fellowship of the Ring (1954), The Two Towers (1954), and The Return of the King (1955).

I fell in love with Middle-earth and high fantasy to the extent that I then read all the supporting material that came out, such as The Silmarillion, Unfinished Tales, The Book of Lost Tales, etc.

I fell in love with Middle-earth and high fantasy to the extent that I then read all the supporting material that came out, such as The Silmarillion, Unfinished Tales, The Book of Lost Tales, etc.

Tolkien’s Middle-earth opened up a world of magic, heroic quests, and history that delved into the beginning of time. It also taught me the importance of building the world a story sits in. Everywhere the characters went, history was imbued in each location. Every character came with their own lineage.

Over the years, I’ve reread the books multiple times, as well as biographies about Tolkien, and some of the additional books that his estate have released.

When the movies were released, I wanted to like them.

And I’ll say that Peter Jackson nails about 90% of the adaptation. The casting is near perfect, the locations are gorgeous, and the unfolding story engrossing.

I appreciate you can’t adapt a book word for word, scene for scene. Changes are needed to condense action. Things that work in a book aren’t always going to work on screen, e.g. in the book the Eye of Sauron is a metaphor; director Peter Jackson transforms it into a strobe light.

I’ll accept these things are narrative necessities, or adaptation flourishes.

My issue is when Jackson needlessly deviates from the books.

Here’s an example of a good change: in the book when Aragorn and the Hobbits are on their way to Rivendell, the Nazgul attack them and stab Frodo. An Elflord, Glorfindel, temporarily joins the party, and later when the Nazgul attack again, Glorfindel has his horse bear the injured Frodo to Rivendell. Glorfindel serves no further point in the story, other than as a reference for the futility of strength in the battle against Sauron.

In the animated adaptation of The Lord of the Rings (1978), Glorfindel is changed to Legolas. This makes sense: Legolas is introduced earlier and we see his friendship with Aragorn.

In The Fellowship of the Ring (2001) it’s Arwen. Again, this makes sense. Jackson introduces a crucial plot point organically: Aragorn’s relationship with Arwen. Also, we see the power of Arwen as an Elf, which helps us put in context her sacrifice when she surrenders immortality to be with Aragorn.

These are good changes.

But there are a number which I loathe, and do nothing for the story.

Here’s just five that have stayed with me …

Merry and Pippin join Frodo and Sam

In the book, Sam, Merry, Pippin, and another Hobbit, Fatty Bolger, know Frodo has the Ring, and are watching him closely, knowing he’s going to leave the Shire at some point to embark on his adventure. Merry and Pippin intend to join him, while Fatty will keep up the pretense that Frodo hasn’t left the Shire. Eventually, the Hobbits reveal their conspiracy to Frodo – Sam has been their spy – and the quartet leave fully prepared for the journey to Rivendell.

In the movie, fleeing a Nazgul Frodo and Sam bump into Merry and Pippin seemingly by accident. This chance meeting entangles Merry and Pippin in the adventure. And off they go.

I know it’s a little thing, but the book’s explanation shows the closeness of the characters, their resourcefulness in their conspiracy and preparing, and how they’re willing to face the risks with their close friend Frodo.

The movie suggests it was just happenstance, which seems a ridiculous motivation as to why Merry and Pippin would get involved on such a tremendous adventure.

Aragorn and Frodo’s Parting

At the end of The Fellowship of the Ring, Boromir tries to forcibly take the Ring from Frodo. Frodo realizes the Ring’s seditious power, and the danger his friends are in if they continue with him into Mordor. Frodo sneaks away. Orcs attack. Sam works out Frodo’s reasoning, and joins him just as Frodo’s leaving in a boat.

Aragorn wants to go to Minas Tirith to help with the coming war, but decides he’ll journey with Frodo to the end. Legolas and Gimli agree.

When Frodo and Sam flee, and Merry and Pippin are captured, Aragorn’s decision is made for him. While he reasons Frodo and Sam have taken a boat, there’s a fear what the Orcs who’ve captured Merry and Pippin might extract from them, so Aragorn, Legolas, and Gimli pursue them.

In the movie, Frodo and Aragorn have one final meeting. Aragorn agrees to let Frodo go on the basis that the power of the Ring will destroy the company.

The motivation is okay, but is it enough?

You have to put this in context: it’s established that if Sauron regains the One Ring, that’s it. They won’t have the power to stop him. All these incidental battles will be irrelevant.

So, surely, if Aragorn had the choice, he’d use his expertise and experience – he has traveled into Mordor repeatedly – to try to ensure that the Ring gets to its destination and is destroyed. Going back to the book, he says he’d remain with Frodo. That’s his intent until the decision is made for him.

In the movie, he abandons his vow to stay with Frodo until the end and wagers two ill-equipped Hobbits can pursue this undertaking alone.

Faramir’s Detour

Faramir and his men capture Frodo and Sam (and, later, Smeagol). Unlike Boromir – who was impulsive and headstrong – Faramir is thoughtful and deliberate. He discerns Frodo is on some important quest. Sam unwittingly concedes they have the One Ring.

In the book, Faramir appreciates the importance of their quest, so he lets Frodo and Sam go on their way, arming them with supplies. It shows how different he is from Boromir, and how he understands that the war against Sauron is a rearguard action to buy time and distract Sauron from his own borders so that Frodo and Sam can slip through unnoticed.

In The Two Towers (2002), Faramir decides to take Frodo and Sam back to Minas Tirith. A Nazgul intercepts them at Osgiliath and there’s a battle. Frodo grows disconsolate. Sam gives him a pep talk about the importance of what they’re doing. Faramir says, “I think at last we understand one another, Frodo Baggins.” Then Faramir releases them to go on their way.

Um, what?

So Faramir takes them out of their way, exposes them to the Nazgul, and then just lets them go because Sam makes a speech?

Is Faramir an idiot?

This makes no sense.

Theoden’s Resurgence

Gandalf, Aragorn, Legolas and Gimli go to the kingdom of Rohan to entreat their aid, only to find the king, Theoden, despondent and resigned. His aide, Grima – who’s secretly in the service of Saruman – has been poisoning Theoden’s mind with talk of hopelessness. Now, Theoden’s only son, Theodred, has also been killed. Theoden sees no way forward.

In the book, Gandalf invigorates Theoden with a stirring speech. Theoden decides he must lead his people and ride once more into battle.

In the movie, Gandalf exorcises Theoden, who’s been possessed by Saruman.

I understand the movie is much more dramatic, but it robs Theoden of any agency in his transformation. He changes because a spell is lifted.

In the book, Theoden makes his own choice. This is a powerful message – that regardless of circumstances, you can take ownership of your own life and choose how you move forward.

Those Lembas Crumbs

While Frodo and Sam sleep, Smeagol takes their provisions of lembas – given to them by the people of Lothlorien – and sprinkles some crumbs on Sam, and tosses the rest over the mountain’s edge. When Frodo and Sam awake and find there are no provisions, Smeagol accuses Sam of eating them all. Sam protests his innocence. Smeagol points out the crumbs on him. Frodo and Sam argue. Frodo condemns Sam. Heartbroken, Sam decides to leave.

This is entirely a movie construct.

The characters are deep inside Mordor, and Sam decides to leave, like home is just around the corner.

But when Sam gets to the bottom of the mountain, he sees the lembas that Smeagol tossed. Sam then has a realization: I didn’t eat the lembas after all!

Sam then goes back up the mountain.

What’s the point of any of this? Would Sam just turn around and go home when they’ve come so far? Was the sight of the lembas really needed to convince him he was innocent? Would he really leave Frodo to Smeagol, when he knows Smeagol is duplicitous, cares only about the Ring, and has suspected the whole time that he’ll betray them?

It’s just pointless drama for the sake of drama and paints Sam as an idiot.

There are lots of little changes like this. Again, I appreciate that adaptation demands innovation. Sometimes, scenes are rewritten. Other times, new scenes are written.

But it goes back to the motivation: what happened in the books would’ve worked fine on screen. Changes like this are lesser choices. They exist to generate needless drama, when there is already enough drama there.

Here’s another example: in The Two Towers, the party is riding to Helm’s Deep. They become involved in a skirmish. Aragorn seems to be killed. The party ride onto Helm’s Deep, grieving. Then Aragorn shows up a couple of scenes later, fine.

This isn’t in the book. Why was it introduced? To introduce some action? We’re about to have this tremendous battle at Helm’s Deep. Do we need this incidental battle? When Gandalf falls, he is transformed from Gandalf the Grey to Gandalf the White. His return means something. Aragorn’s means nothing.

If you chopped Gandalf’s fall, you wouldn’t understand why he’s no longer involved with the party, why they grieve him at Lothlorien, why his return inspires hope, why his rise recontextualises his relationship with Saruman, and why he has changed.

If you chopped Aragorn’s fall … well, it does nothing, other than render a few peripheral references confusing. They become redundant anyway when he does show up at Helm’s Deep.

If you don’t know these things have been changed, I guess they play out fine.

My issue is that these narrative choices feel like they amount to cheap gimmickry, rather than being causal and motivated, as they are in the books.