James … who?

As I grew up with James Bond in the 1970s, there were two entrenched Bonds: Sean Connery and Roger Moore. The question that hovered over them was, Who is your favourite Bond?

I couldn’t pick. I’d flip to whoever’s movie I was watching. I like Sean Connery’s calm, ruthlessness, and accent, while I enjoy Roger Moore’s affability, suave, and polish.

I couldn’t pick. I’d flip to whoever’s movie I was watching. I like Sean Connery’s calm, ruthlessness, and accent, while I enjoy Roger Moore’s affability, suave, and polish.

My brother told me about another Bond, George Lazenby, who made only one picture, and was a closer fit to author and creator Ian Fleming’s template.

I was still just a kid when I finally saw On Her Majesty’s Secret Service (1969), but I liked it. I think Lazenby is unfairly criticised. He’s the first Bond asked to go off and do his own thing (as in he’s not issued a mission), he falls in love, and he behaves like a fop (and is dubbed) for a big chunk of the film – these are not stereotypical Bond behaviours, so the character strays from familiar Bond territory. This movie – and Lazenby – are underrated.

Through the 1980s, I continued to grow up with Roger Moore. Moore had been the original choice for Bond, but had been contracted to the television series The Saint (1962 – 1969), so Connery got the gig. This meant Moore walked into Bond late, and he started to show his years early in his tenure.

Connery had complained that the movies were becoming too reliant on gadgets. That’s something that continued throughout Moore’s tenure. And, although he could be cold and ruthless when required (although never with Connery’s casual underlying menace), Moore’s Bond gravitated away from that tonally and became lighter and, sometimes, frivolous.

Apparently, For Your Eyes Only (1981) was meant to be Moore’s last Bond. James Brolin was going to succeed him in Octopussy (1983). However, Connery was signed to play Bond in a renegade James Bond movie, Never Say Never Again (1983). The Bond producers grew worried Connery would trounce a new Bond actor, and thus re-signed Moore. When the two Bond movies came out, Octopussy triumphed over the renegade Never Say Never Again.

Most people I know dislike Never Say Never Again. I like it. It tries to take into account that Bond’s aged, and he’s now a relic in a world of espionage that’s moving past him. Domino Petachi (Kim Basinger) and Fatima (Barbara Carrera) are good as Bond’s love interests, and Klaus Maria Brandauer enigmatic as arch-villain Maximilian Lago.

Moore hung on for A View to A Kill (1985), which would’ve been a great Bond for a new actor. It had a wonderful villain in Max Zorin (played by Christopher Walken), a fantastic henchperson in Mayday (Grace Jones), and the adventure was powered by Duran Duran’s titular song, A View to a Kill. Moore definitely shows his age, though.

When he finally retired, different actors were approached. Pierce Brosnan was just finishing up on his TV series, Remington Steele (1982 – 1987). He was set to become the new Bond, but the buzz around the announcement rejuvenated Remington Steele for another season, and thus he missed out. I recall Australia’s Andrew Clarke was also approached, but allegedly baulked at a ten-year contract. They settled on British actor, Timothy Dalton, who’d originally been approached after Sean Connery had left, but had thought it would be ‘daft’ to try follow in Connery’s footsteps.

That’s an interesting perspective. Nowadays, Connery tends to be remembered as the best of the Bonds. It also makes the kerfuffle surrounding his departures an interesting footnote. Connery left following You Only Live Twice (1967), which gave Lazenby the unenviable job of succeeding him in On Her Majesty’s Secret Service (1969). Lazenby then left, and Connery came back for Diamonds are Forever (1971).

Diamonds has one of the great openings as Bond – wanting revenge for the murder of his wife in OHMSS – wreaks havoc to track down Blofeld (Charles Gray). But then the movie becomes a weird pastiche of tone and aesthetics, and Connery himself looks vastly disinterested.

In hindsight, the activity that surrounded these three movies helped demythologise Bond so they could soft reboot with Roger Moore, and it made it easier for the public to accept a new actor, and a new direction.

Anyway, so now we have Timothy Dalton. With his debut outing, The Living Daylights (1987), there’s a concerted effort to ground the series after Moore’s sillier adventures. Also, due to the sexual climate at the time (and concerns about AIDS), Bond’s not going to be a rampant womaniser. Instead, he’s going to have only one love interest in the film, Kara Milovy (Maryan d’Abo). The villains are competent without being spectacular. The script was written specifically for Brosnan, then revised for Dalton. It’s really a story in which the filmmakers are trying to feel their way into a new era and reconnect Bond to his grittier roots.

License to Kill (1989) follows – a story which pits Bond against a drug baron. It seems hardly worthy of Bond’s time, a vendetta he should be able to execute in his lunch hour. But it’s darker and Dalton feels more comfortable with the role, and Robert Davi provides a good antagonist as Franz Sanchez. It’s a hugely underrated Bond because it’s a story that focuses purely on revenge, rather than espionage, or villains trying to take over the world.

I am a huge fan of Dalton. He gets lost in the Bond discussions. For years, Bond had a monopoly on big action movies. Dalton’s Bonds came at a time that Hollywood learned that the big action blockbuster was a thing to be exploited. Lethal Weapon (1987), Lethal Weapon 2 (1989), The Last Boy Scout, various Arnold Schwarzenegger and Sylvester Stallone vehicles, their clones (e.g. Steven Seagal, Jean-Claude Van Damme, Dolph Lundgren), etc., were hitting the big screens – and a lot of these movies were doing action better than Bond, which was struggling to find its way.

Aficionados of the novels laud Dalton as the closest interpretation of Fleming’s Bond. Dalton has Connery’s ruthlessness, but arguably not his easy charm. It would’ve been awesome to see him grow into the role and given meatier movies to star in.

Dalton was interested in taking the best of his two movies and making a spectacular third movie. Unfortunately, it wasn’t to be as EON Productions and MGM entered a protracted legal dispute over rights, interrupting pre-production on Goldeneye (1995). By the time pre-production resumed four years later, Dalton was interested in doing only one more movie. Given what would be a six-year hiatus between movies, producer Albert Broccoli said Dalton would have to do another four or five. Dalton decided to pass and the role went to Brosnan. The script was then revised to suit Brosnan.

Goldeneye is the best of the Brosnan Bonds. The rest are campy and silly, degenerating into stupidity like invisible cars. Brosnan is a good actor – watch him as a ruthless spy in The Tailor of Panama (2001). That’s how his Bond should’ve been written. Unfortunately, he didn’t get it. It’s like they had misgivings about the tone they (try to) set with Dalton, and were now resurrecting what they’d had with Moore because that had been popular and safe. Brosnan desperately wanted to be Bond and lamented when he’d originally missed out, but as his tenure goes on he seems to grow ambivalent.

As an aside, I saw a movie in 1999 entitled Croupier (1998), starring Clive Owen. Owen was unknown to me, but seeing his performance in that movie convinced me he would be a brilliant Bond. Several years later, he starred in a series of short films that BMW (yes, the car company) produced playing a Bond-like character. This also boosted his currency – well, as far as scuttlebutt went. Owen claimed he was never approached. Instead, the role went to Daniel Craig. But watch these shorts and decide for yourself if Owen would’ve been a good Bond.

The filmmakers must’ve realised they’d strayed into farce, because they decided on a hard reboot. I don’t get this. Bond has been repeatedly soft-rebooted for each new actor. Why do we need to wipe history clean to introduce Craig – especially when it makes no impact on the storytelling? Nothing happens in Casino Royale (2006) that needed the hard reboot. Why not perpetuate the affectation that Bond is timeless, even if events in his life (e.g. his marriage) are dated?

They do go for a grim aesthetic – precisely what they tried with Dalton – and try to introduce a new organisation, Quantum, which then falls away. Then they resurrect and disassemble SPECTRE within the space of a single movie. While Moonraker (1979) is arguably the stupidest Bond – well, the first half is actually very good; the second half is space fantasy inspired by the Star Wars: A New Hope (1977) craze at the time – it’s now succeeded in the stupidity stakes by forging a familial connection between Bond and Blofeld (Christoph Waltz).

I love the ideal behind James Bond – a spy who saves the world from megalomaniacal villains. He just about always has a witty comeback, and an array of gadgets to save him. He’s a superhero. But the truth is that of the twenty-four existing movies, there’s only a handful of great ones, a handful of good ones, and the rest are middling, often lost in tonal inconsistency, contemporary influences, and uneven plotting.

It feels as if Bond has lost his identity – that flirtation with his origins in Casino Royale aside. You can go watch a new Mission: Impossible adventure and greet those characters and that world and its challenges with familiarity. This is a strength. Bond just seems to shift from thing to thing to thing, trying to discover what’s made it this cultural icon that’s connected with the people, and then guessing haphazardly about how to duplicate that tone through a contemporary filter, but never really seeming to understand it.

While I appreciate that real-world events (e.g. the end of the Cold War) have impacted Bond’s standing in to the world, it shouldn’t be that hard to transfer villainy, or maintain an independent terrorist organisation such as SPECTRE, or keep Bond true to himself. These are the ingredients that created a cultural icon who’s survived for over fifty years, while other franchises have fallen by the wayside.

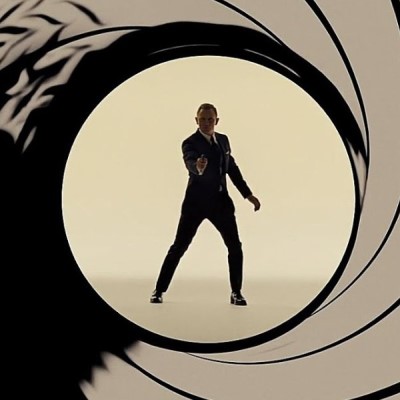

This is who Bond is.

Who he’s meant to be.

I really don’t know who or what Bond is anymore – and, sadly, that’s something I think has been an issue for a while.